While not as iconic as its landmark neighbor the Marston Water Tower, a historic structure that has been part of the College of Engineering landscape for many decades is about to meet its end. Known as “Old Sweeney,” the structure that extends from the southeast corner of the current Sweeney Hall, along with the nearby Nuclear Engineering Building, will soon be reduced to rubble to make way for the new Student Innovation Center.

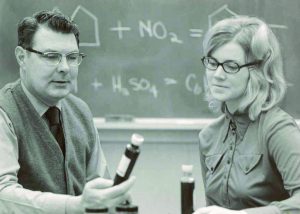

Once the home of Iowa State’s chemical engineering department for nearly 40 years, Old Sweeney holds its share of memories for those who have worked, studied and conducted research in it; and for two Department of Chemical and Biological Engineering faculty members, Anson Marston Distinguished Professor Emeritus Dr. George Burnet and University Professor Emeritus Dr. Thomas (Tom) Wheelock, they have done all three. On the eve of Old Sweeney’s destruction, they discussed days gone by in the structure that played a key role in the evolution of a department and curriculum.

In the time following World War I chemical engineering was a rapidly expanding frontier in the United States, and a growing curriculum at Iowa State University. Orland Russell Sweeney, the namesake of Sweeney Hall, became the first head of chemical engineering at ISU in 1920, after being assured an autonomous chemical engineering department would be established, instead of being tied to the chemistry department, as it was at the time. In light of that, the “Chemical Engineering Building” opened to house the new department seven years later.

George Burnet walked through the doors of the Chemical Engineering building as an undergraduate chemical engineering major in 1942. He then put his studies aside and volunteered for the Army in 1944 and served in the South Pacific. He returned to Iowa State to finish his bachelor’s degree in 1948; he earned a master’s at ISU in 1949 and Ph.D. in 1951. After working in industry he returned to his alma mater as an associate professor in charge of unit operations and became department head in 1961.

Tom Wheelock interrupted his undergraduate chemical engineering studies at Iowa State in 1943 to serve the war effort in the U.S. Navy. He returned to ISU after the war and received his B.S. in 1949. After spending time in industry he returned to ISU for graduate school in 1954 and received his doctorate and joined the faculty in 1958.

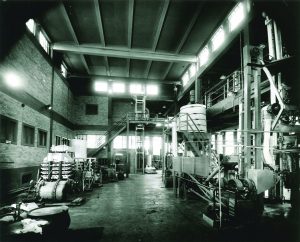

It is perhaps ironic, yet fitting, that Old Sweeney and the Nuclear Engineering Building will fall into history together. Unknown to many, the “NukeE Building,” as it is often called, was originally called the West Chemical Engineering Building. It was built in 1935 as a USDA Research Laboratory and was a key part of the earliest chemical engineering work on campus. Sweeney was heavily involved with the use of agricultural bi-products in his early years at ISU, and “The USDA built that building to expand Sweeney’s ag bi-product research,” said Burnet. “Sweeney was interested in uses for soybeans. At that time soybeans were being imported from China and the expelling process they used for extracting ingredients was not very efficient – so Sweeney started looking at ways to do a more practical chemical extraction.” The building became home to a 10-ton per day soybean extraction facility that was used as a pilot test plant for

creating soybean oil meal for feeding to livestock. Unfortunately, widespread death of cattle from eating the original meal led to changes in extraction techniques. Many Iowa State chemical engineering students wrote theses on this topic.

But it was in the nearby Chemical Engineering Building where the majority of the long-term education and research was performed. The chemical engineering department was originally housed in the basement of Gilman Hall. But when the new Chemical Engineering Building went up in 1927 there was a great exodus of people and equipment to the new dedicated structure. An architect’s rendering of the building ran in the Des Moines Register with the bold headline, “Iowa’s prosperity may be determined in this building.” It cost about $70,000 to build.

“There was just one classroom in there,” said Burnet, “and it held about 30 people. So classrooms in other locations had to be utilized.” That problem was solved with the addition of a north wing to the Chemical Engineering Building completed in 1931 that provided more classroom space, in addition to offices for the chair, staff and others. Today it is the one-story segment of the structure that connects with the southeast corner of Sweeney Hall. Burnet recalled a memorable feature of the north addition: something called a “jack shaft,” a large rotating shaft that hung from the ceiling and ran the length of the building. “If you wanted to power something in the building, such as a motor, you’d attach one end of a belt to what you wanted to run and attach the other end to that rotating jack shaft, and there was your power source,” said Burnet.

“The original large building was mostly labs,” Wheelock recalled. “It had a large open bay in the center that encompassed the whole second floor. Sweeney developed it that way so that he could have the space to demonstrate uses of many different products he constantly worked on.” Just a few of those projects Sweeney and company developed in that building included Maizewood, an insulting board made from cornstalks, which was demonstrated at the Chicago World’s Fair in 1933; hardwood made from cornstalks; Maizolith, or “cornstone,” a product that could be processed into a substance with great strength; and furfural, a compound of formic acid made from corncobs that had many uses in manufacturing products.

The department head had an office, but it was not “exclusive real estate.” “It served many purposes,” said Burnet. “It was used for things like Ph.D. presentations and meetings of all kinds. There were no conference rooms like today.”

Another favorite memory for Burnet involved difficulty keeping his office clean. “In the fifties there was no air conditioning in the building,” he said. It had large Steelcase windows you would swing open for air. At night in hot weather when you’d go home you’d leave the windows open so cooler air would come in. Problem was, there was a parking lot nearby, where The Durham Center is now. The lot was paved with cinders and they’d float around on the wind. I’d come in the next morning and have to clean all the black dust off my desk.” Wheelock added that those large windows also made an attractive entryway into the building for birds. “The sparrows were always coming in and messing up the furniture,” he said.

Then there was the elevator: “There was an elevator that went from the first floor to the second floor,” Wheelock commented. “It was hand operated. You pulled a rope to make it go up and down.”

But perhaps the biggest conversation piece in Old Sweeney was the fire pole. Just like what can be found in fire stations, the brass pole was installed to allow quick exit from the second floor in the event of a fire. “There was a railing around the perimeter of the big opening on the second floor, like a balcony,” Burnet explained. “In one spot next to the pole there was a gate. You’d open the gate, reach out, grab the pole and slide down.” As you’d expect, a fire pole designed for emergency exit also made for an attractive way to quickly get from the second floor to the first under normal circumstances. It was said that

Sweeney himself would often surprise visitors to the building by sliding down the pole, nattily dressed in his trademark gray suit. Students, too, “Would sometimes take advantage of the pole, even though they were not supposed to,” said Burnet. When asked if faculty over the years ever did the same, he just smiles and shrugs. Question answered.

Sweeney was a big believer in efficiency of design and use of resources. Drains for water and other fluids were strategically placed in the building, and the concrete floors were correspondingly sloped toward the drains – so much so that it was noticeable when one walked across the floor. “When you walked through that building you were always going up and down. People would always comment about it,” said Burnet.

And outside the building was another favorite sentimental spot: A large pile of discarded heavy laboratory equipment. Called “Sweeney’s junk pile,” Sweeney would vigorously defend its existence as a good source of parts for research. Though the “junk pile” eventually went away when a storage building elsewhere was put up, the tradition was apparently revived by Henry Weber, who was a faculty member from the late 40s to the mid-60s. Burnet said in the same spot on the west side of the building was what was called “The Bone Pile,” a large collection of things like pipes and fittings. “If you needed something for your research you went out to the Bone Pile and you could find what you were looking for,” he chuckles.

Construction of the original portion of today’s Sweeney Hall began in 1962 and the building was dedicated in 1964. Much of the department’s functions moved to the new Sweeney Hall, though Old Sweeney was retained and used for many years. In more recent times it became home to a variety of interests, including a wind turbine research program, the ISU solar car race team, Team PrISUm and much more.

When Old Sweeney and the Nuclear Engineering Building meet their demise in demolition that is tentatively set to begin May 8, space will be opened for the new Student Innovation Center, which will allow study, collaboration and creation. And thus the same Iowa State University spirit and tradition that was fostered within the walls of the original structures will be continued inside those that will shine brightly with new promise into the future.