More than a century ago, Iowa State’s campus grappled with a pandemic that it had never seen before.

In August 1918, a Spanish flu outbreak hit at a time when the world was already engulfed in the final months the First World War. Even Ames, Iowa, saw the economic and cultural impact caused by both the war and the flu outbreak.

In August 1918, a Spanish flu outbreak hit at a time when the world was already engulfed in the final months the First World War. Even Ames, Iowa, saw the economic and cultural impact caused by both the war and the flu outbreak.

By late September 1918 (a little more than a month before the end the war), the flu had spread to Iowa. Iowa State College’s State Gym was converted from an athletics facility into a makeshift hospital to accommodate all of the flu cases on campus.

During this time of great volatility, the college’s top administrator was Edgar Stanton, who was acting president (his fourth stint in this capacity) while President Raymond A. Pearson was serving in the U.S. Department of Agriculture as part of the war effort. Stanton was the first graduate of Iowa State when he completed his degree in mechanic arts (predecessor to mechanical engineering) in 1872.

On Oct. 1, 1918, the second day of class that quarter (Iowa State was on a quarter system until 1981), Stanton penned a letter in the Iowa State Daily welcoming back students. He maintained a mostly positive, encouraging tone in his letter, despite all of the hardship occurring across campus and the nation.

GREETING From Acting President Stanton

Here’s to the men and women of the higher classes who have returned to the old Campus. Your ranks are thinned; familiar faces are absent; on land and sea, in camp and in on the fields where bloody war runs riot today, your classmates and the sons of I.S.C. [Iowa State College] are periling their lives in the cause of human liberty. You men are here at the bidding of the government, making ready to render service when and where the war department shall direct. The College has ever been a milestone to brave hearts on the way to the highest duty. It should be and will be such to you in a new and [fuller] sense than ever returning student faced before. You will, I know, in the spirit of earnest devotion that goes with these years, meet and do the work that lies before you.

Here’s to the men and women of the higher classes who have returned to the old Campus. Your ranks are thinned; familiar faces are absent; on land and sea, in camp and in on the fields where bloody war runs riot today, your classmates and the sons of I.S.C. [Iowa State College] are periling their lives in the cause of human liberty. You men are here at the bidding of the government, making ready to render service when and where the war department shall direct. The College has ever been a milestone to brave hearts on the way to the highest duty. It should be and will be such to you in a new and [fuller] sense than ever returning student faced before. You will, I know, in the spirit of earnest devotion that goes with these years, meet and do the work that lies before you.

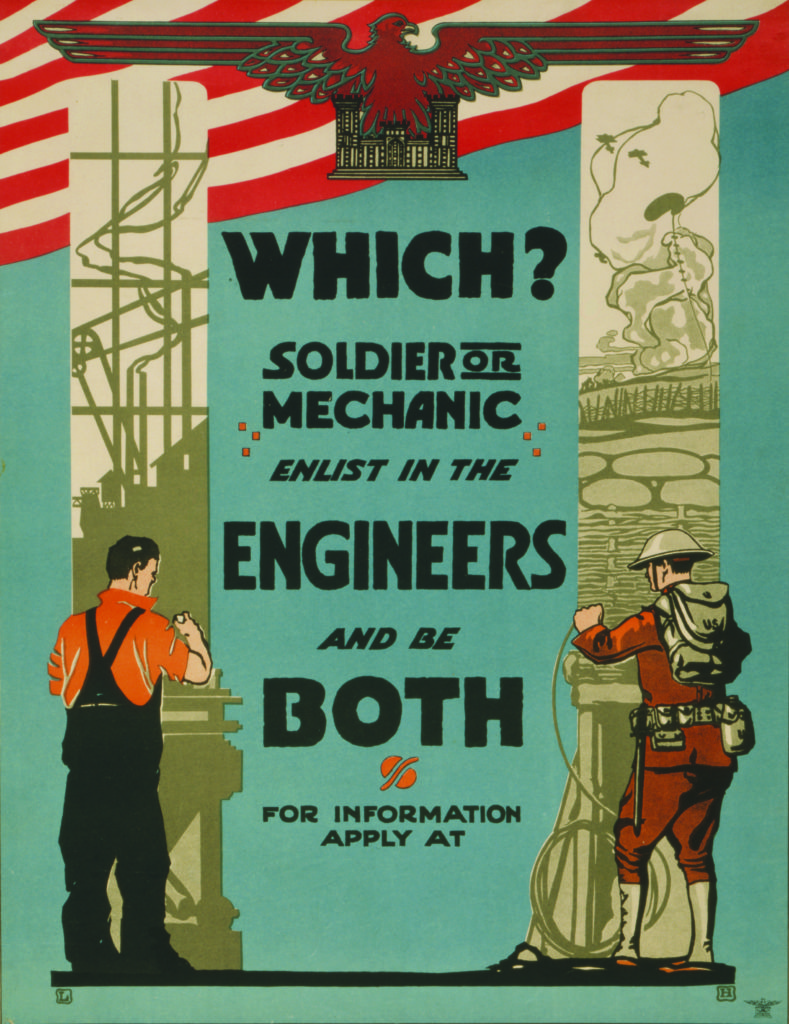

To the multitude of young men and women who join our rank today we extend a special and most heartfelt welcome. Yours is an uncommon coming. To most of you, it is entrance into the life of a student and the life of a soldier; to all it is a call to the colors—a summons weighted down with responsibility and obligation, but opening up at the same time privilege and opportunity that have no limit. We greet you with a tender heart and an open hand. You become today one of our number—part and parcel of a great enterprise dedicated to the making of manhood and womanhood, and loyal citizenship for the nation. You are to live in an atmosphere and among men already pledged to good fellowship and good purpose. It is yours to take up with sincerity and courage the privileges and duties of the hour, enter into the ideals and traditions of the institution, and, as you make a better self, help to make a better College.

Here’s to the cardinal and gold and the student body which is to see to it that that flag and old glory shall wave at Ames over a College that in scholarship and moral worth and patriotic ardor shall rank among the first in the land!

Go to it, my friends!

In the coming days, Stanton and other administrators handled the situation with the utmost seriousness and professionalism. Unfortunately, not everyone in Ames took the threat seriously, and crowds poured out onto Main Street in downtown Ames around 1:30 a.m. on October 6 to celebrate rumors that the Germans wanted peace talks with the Allies. This occurred at a time when mass public gatherings were discouraged.

On Oct. 9, 1918, Stanton penned a letter to the Committee on Education and Special Training in Washington, D.C. stating:

We have some 300 cases of the Influenza, but have ample hospital facilities, physicians and attendants. The number of new cases are decreasing, those discharged from the hospital exceed those admitted, and we feel that we are facing toward normal conditions. We have a strict quarantine separating us from the rest of the world.

Shortly after, he wrote a memo for department heads at Iowa State stating, “At meeting of the Board of Deans on October 8, 1918 it was decided that, for the time being, complete segregation of men from women students be established, including segregation at class periods.” There was little mention of the of this female quarantine in the local press at the time, and to this day it is unclear why students were quarantined by gender.

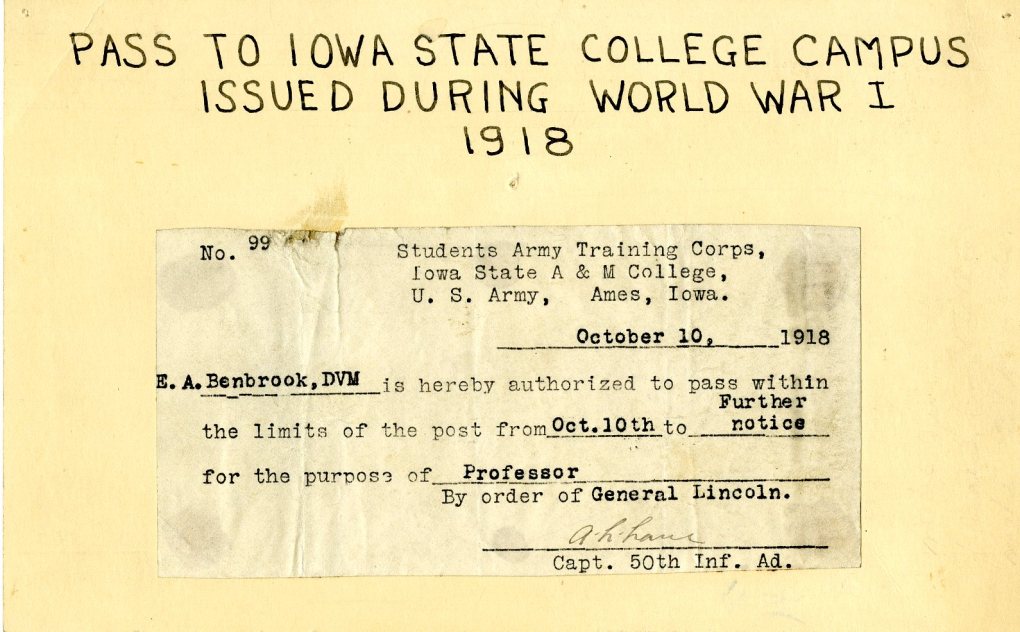

While the campus was on quarantine (which began on October 2), guards monitored the perimeter “24 hours a day, 7 days a week.” Those looking to enter or leave campus required special permission and were granted a pass that they needed to present to the guards. Football games and most other social activities were canceled.

Records from the Iowa State’s hospital show that 669 flu patients received treatment during the first half of October. In the end, 53 people at Iowa State perished because of the flu outbreak. Two of the deaths were women, while the other 51 were men serving in the Student Army Training Corps (SATC). The names of the SATC men are enshrined in the Gold Star Hall inside the Memorial Union.

Edgar Stanton, or “Stantie” as students affectionately called him, would pass away in 1920 at the age of 69. His death was attributed to a combination of the Spanish Flu (which he contracted in 1918) and diabetes. He served his alma mater for nearly half a century, from the day he graduated and was hired to the faculty in the mathematics department until the day he died when he was serving as the college’s vice president. He is buried in Iowa State’s cemetery and prior to his death Stanton Avenue in campustown was named in his honor.