This feature debuted in the Spring 2013 issue of ECpE Connections Magazine

Brian Kraus, Robert Romore, and Jacob Cramer are architects, but they don’t build museums. They’re designers, but they don’t lay out magazines. They work with physics, but they’re not physicists. All three are software engineering majors, but they consider themselves game developers at heart. Kraus, Romore, and Cramer build worlds, design characters, and program how they move with a few keystrokes and a lot of dedication.

Last May, the three joined with computer engineering major Brittany Oswald and others to found the Game Development Club (GDC), a student-run organization established to provide students with knowledge and support for game-related projects. The club, which has swelled from the four founding members to more than 170 in nine months, offers students the opportunity to experiment with a variety of game design tools.

“Plenty of students are interested in making video games,” Oswald says. “There are lots of tools that are available that students might not be aware of. If we can teach some of these tools to students, or even just bring awareness to them, we can go a long way.”

Game designers use a variety of tools to make their worlds come alive. The most important of these tools is the game engine, which serves as a framework for the game. The engine dictates how graphics are rendered, how physics are handled, how characters animate, and much more. Currently, one of the most popular game engines is the Unreal Engine, which was used in the development of top hits like Borderlands 2, Mass Effect 3, and XCOM: Enemy Unknown in 2012.

“We’ve introduced the Unreal Engine,” Cramer says. “But it’s a little complicated for beginners. Things like Unity, are a lot easier to get into and are a lot friendlier.”

Unity, originally launched as a Macintosh-only platform in 2005, has grown to become the engine of choice for mobile game developers. According to Gamasutra, a site that focuses on game development, more than half of all mobile developers use Unity, making it the perfect engine for Kraus, Romore, Cramer, and Oswald to start with.

“We use Unity a lot,” Oswald says, “but we also get into things like XNA, which is a C# development framework, Stencyl, and others. We try to make things as inclusive as we can.”

The group doesn’t only teach basic software skills. Often, the meetings include discussions on game design principles or larger, philosophical issues; such as the role of violence in games. Meetings can be hours of coding, but just as often they turn into a vibrant discussion on the merits of certain games and design elements.

Part of the group’s purpose, along with teaching design tools and fostering discussion, is to actually make games, and teams within the club are doing just that.

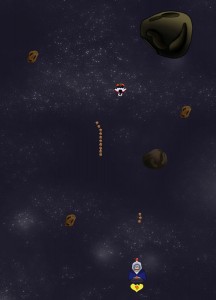

SPACE SHOOTER

Zach Plata is a composer, but he’s not a music major. Plata is a freshman in the software engineering program and joined the club to compose video game music.

“It’s very open,” Plata says of the GDC, “There are lots of resources that we use and explore. Something I like about the GDC is that they let me focus on the musical aspect.”

Plata uses Finale, a composing program, to arrange music.

“It’s kind of like a blank palette,” Plata says. “You just click along notes and figure out what kinds of sounds you want to use, instrumentation, that kind of thing. From there I can figure out what the team needs me to do. It’s really easy just to let my imagination go.”

Plata’s musical talents and software engineering know-how make him a valuable asset to any would-be game design team. Kraus, Romore, and Cramer recruited him to help with their top-down mobile space shooter project, Spudnik.

“One of the things from last semester was NaGaDeMo (national game design month), where you make a game in a month,” Kraus says. “The easiest way to describe [Spudnik] would be like a bullet-hill shooter, where you’re at the bottom and you dodge asteroids as they fall down. Also, it’s important to know that you’re an astronaut potato, which is where the name Spudnik comes from.”

The team emerged from the larger club and began work on Spudnik last summer. The team thought its astronaut potato angle was funny enough to work, but the project came together when one of Kraus and Romore’s friends came up with the name.

“We knew we had the astronaut potato idea, and we were walking to lunch trying to think of a name,” Kraus says. “One of our friends stopped mid-stride and said ‘wait for it…Spudnik.’ And our minds were blown right there.”

The team made enough progress on the game that month to produce a playable demo with finished graphics and controls. Work continues on Spudnik, but the team is already branching out into other, more involved, projects.

“I’m wanting to develop a really complex game,” Romore says. “My idea is a Minecraft-type game, but it would be set out in the universe. So you’d have a revolving planet with stars and stuff.”

The group has different ideas on what to do next, but for them, that’s what makes gaming so interesting in the first place.

TALKING GAMES

Video games are a malleable art form. They can take on any task and perform to any requirement the designer puts on them. It’s no wonder, then, that the founding members of the GDC can interpret and appreciate the same game in such different ways.

“I recently started playing Dark Souls again,” Cramer says. “It’s really deliberate and there’s a lot of really subtle storytelling in there. They don’t tell you anything, but there’s a lot of story stuff that’s happening. If you want it you can have all of that, but if you don’t you can just play.”

“That’s a game,” Kraus says of Dark Souls, “That if you play for too long a time, it starts messing with your head. It can be suffocating. I really respect how they did that.”

“I like Dark Souls, but that’s a game that I like for the concept of the game,” says Oswald. “I wouldn’t play it – I don’t like being afraid – but I’ll watch as someone else plays and appreciate the design.”

Oswald, in particular, has her sights set on using games and game design for more than just amusement.

“I want to make games that are beneficial for people, for teaching and learning,” she says. “It’s not just pure entertainment. There’s a lot of potential to use it for more than just entertainment. For instance, I’m interested in virtual learning environments and how video games and virtual worlds can be better utilized in education.”

Making a game, educational or just for fun, can be rewarding, but it can be a difficult and sometimes tedious prospect. The Spudnik team advises would-be game designers to expect this from the start.

“Right from the beginning, it really was much more tedious than we thought it would be,” he says. “We were all excited and thinking ‘we’re going to make a game, it’s going to be cool.’ But it takes a lot of time, and you have to be prepared for that.”

The work involved in making a game can be overwhelming, but it can be worth it for a particularly good idea. The Indie game scene on download services like Steam and Xbox Live Arcade can be a particularly friendly environment for good games.

“With all the tools that are available,” Kraus says, “it’s pretty cool what you can accomplish by yourself. It’s exciting, getting into development now, knowing that if your idea is good enough that you could be the next Notch [Markus Persson, creator of Minecraft] or something like that – totally self-made.”

All this hard work is driven by passion, and passion comes from experience. Each member of the team can cite specific games that displayed to them the promise of the medium. Everyone’s game or moment is different, a fact that only adds to the inherent flexibility of the medium.

“The one for me is Zelda: Ocarina of Time,” Romore says, “After I played that, I was just enthralled with video games. It’s what introduced me to all the things that are possible.”

“My favorite game growing up was Twisted Metal,” Kraus says. “My cousins and I would play it when I was really little.”

“I used to be a big fan of Final Fantasy,” Plata says, but one of the biggest things that got me hooked was Mega Man Legends. I was really captivated by the whole adventure and that’s what really got me started in games.”

A good idea and some dedication can go a long way in the GDC. Still, Cramer offers a final piece of advice for would-be developers.

“You just have to get started.”