Photo courtesy of Robert C. Brown.

When he’s not busy conducting research in the laboratories of the Bioeconomy Institute on the Iowa State University campus, Robert C. Brown might be found working in another lab he has inside his home. This one happens to be a brew lab.

Brown, director of Iowa State University’s Bioeconomy Institute, is among the roughly 1.2 million Americans who brew their own beer. Brown said that he came of age before the craft brewing revolution and had little interest in the traditional lagers (Budweiser, Coors, Miller, etc.) that dominated the beer market at the time.

Being an experimentalist, Brown decided not to strictly adhere to the ancient German beer purity law of “Reinheitsgebot” which decrees only four ingredients be used in beer brewing – barley malt, hops, water and yeast – when he began brewing his own beer.

“With respect to the Reinheitsgebot, I am a scofflaw, frequently employing oats, wheat, rye, fruit, brown sugar, spices, peppers, chocolate and even bacteria in my brewing,” said Brown, who also serves as Anson Marston Distinguished Professor in Engineering and Gary and Donna Hoover Chair in Mechanical Engineering at Iowa State.

A family matter

For Brown, homebrewing is a family matter. It was his three sons who first introduced him to craft beer roughly 12 years ago. Brown said that he was “pleasantly surprised” with the variations he tried and was intrigued by the fact that some of these variations had been in existence for a century or longer, prior to making a resurgence in the United States with the craft beer revolution over the past couple decades.

After a couple years of enjoying craft beers, Brown and his sons decided to take the next logical step and began brewing their own beer.

“For a while, my wife tolerated us in the kitchen but today I have a dedicated brew room in the basement with a gas stove top, utility sink and three freezers with temperature controllers used in fermenting, lagering and dispensing beer,” Brown said.

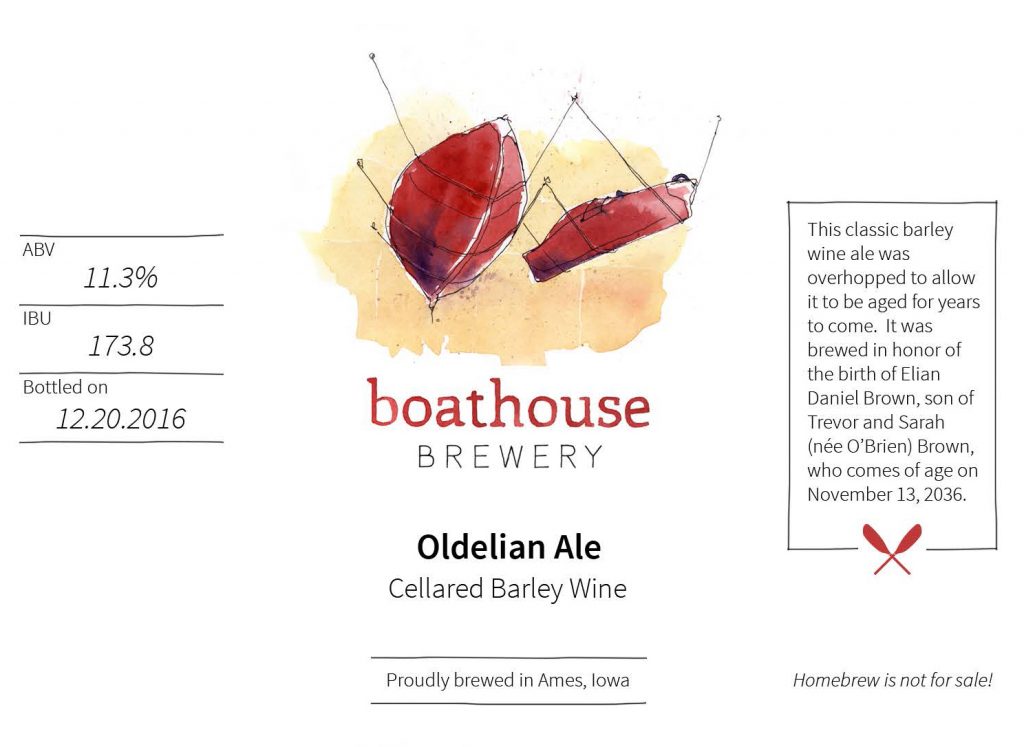

Brown’s middle son, Trevor, a trained artist, designs the labels for the beer they brew. These labels include original artwork created by Trevor as well as details about the beer and even a clever description for each brew. Upon the suggestion of his eldest son, Tristan, Brown brews a batch of strong ale for cellaring upon the birth of each grandchild. The adults in the family open a bomber (22-oz bottle) each year with the last bottle timed to be opened when each grandchild comes of age. To survive the cellaring process, these brews have exceptionally high alcohol by volume (ABV) percentages. Brown currently has four grandchildren and a unique brew for each of them.

The beer brewing process

Brown said he spends at least six hours when preparing an “all grain” five-gallon batch using malted grains. This includes grinding the grains; mashing them to produce a sugary wort; boiling, hopping, and cooling the wort; filling and aerating a fermenter; pitching yeast or blends of microorganisms into the wort; and cleaning up. He added that there is some prep he does the day before he starts a new batch, which involves adjusting mineral content of the brew water and making a yeast starter.

Small batches using malt extract eliminates the grain mashing step and can be completed in less than half the time. However, the final fermentation step takes anywhere from one week to over a year before the beer is ready to drink, depending upon the choice of microorganisms and the style of beer.

Photo courtesy of Robert C. Brown.

The process differs depending on the type of beer he’s brewing. Beer brewing roughly breaks down into room temperature fermentation with “top fermenting yeasts” to produce ales and cool fermentations with “bottom fermenting” yeast to produce lagers, according to Brown. He has recently begun experimenting with “hot fermenting” yeast at temperatures approaching 90 degrees Fahrenheit, which speeds the conversion of sugar to ethanol without compromising product quality.

“Part of the fun of brewing is exploring new combinations of ingredients. For example, this past summer I concocted a jalapeno sour ale, which is initially fermented with lactobacillus, the same bacteria used to make yogurt, in a wort boiled with fresh jalapenos,” Brown said, adding that he also brews the more familiar and easy drinking beers like pilsners and wits.

“In the corner of my basement brew room is a glass carboy of slowly fermenting beer that is home to wild microorganisms that had contaminated one of my conventional beers years ago but are now harnessed to produce a Lambic-like beer,” said Brown.

For those looking to pursue their own adventures in homebrewing, Brown offers some advice. First he said it can be helpful to befriend a veteran homebrewer willing to show a rookie the ropes. Alternatively, he said, John Palmer’s book “How to Brew” is an effective guide for the novice homebrewer. A large kitchen pot can serve as a brew kettle and most of the other necessary equipment can be purchased for less than $50. Raw ingredients for a five-gallon batch range from $25 to $50.

Parallels to engineering research

Prior to the advent of technology like thermometers, hydrometers, and precision weight scales, Brown, a distinguished professor with appointments in mechanical, chemical and biological, and agricultural and biosystems engineering, said brewers often approached brewing as an art rather than a scientific process. He thinks engineers can apply techniques and knowledge from their field to improve the homebrewing process.

“I see misperceptions among the homebrew community ranging from how long it takes to drive-off sulfur compounds while boiling lager wort to the role of nitrogen in producing the creamy colloidal foam of beer on nitro,” Brown said.

Brown said that the parallels between homebrewing and his particular research, is “closer than you might think.” Successful homebrewing involves the conversion of starch polymers in grains into simple sugars to form a fermentable solution, while Brown’s research in bioenergy focuses on the conversion of cellulose polymers in biomass into simple sugars to form a fermentable solution.

“I have brewed dozens of beers at home from starch-derived sugars but so far only one beer from biomass-derived sugars produced on campus, which I am afraid was not drinkable,” said Brown. “But the same could be said of my first homebrewed beer. On more than one occasion, a weekend of homebrewing has inspired ideas for my research on campus.”

Last year Brown was awarded a multimillion dollar grant from the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) to develop a system to convert plastic and paper wastes generated by the military into macronutrients to feed expeditionary forces. Brown and his team are using a thermal process to convert these wastes into substrate for fermentation into single cell protein. The team not only has to prove out the basic concept, but they eventually need to build a field deployable fermentation system that is simple enough for soldiers to operate.

“The constraints to this problem have several parallels to homebrewing. As I told our team, I have been preparing for this project for the last ten years,” Brown said.

Mark your calendar!

Dr. Brown in partnership with the Center for Crops Utilization Research (CCUR) at Iowa State University plan to offer a homebrewing workshop later this year. Organizers hope to have a syllabus developed and the necessary equipment purchased so the workshop can be offered in the fall.

For more info about this event, contact Zhiyou Wen at wenz@iastate.edu