This story was originally published with the Iowa State News Service.

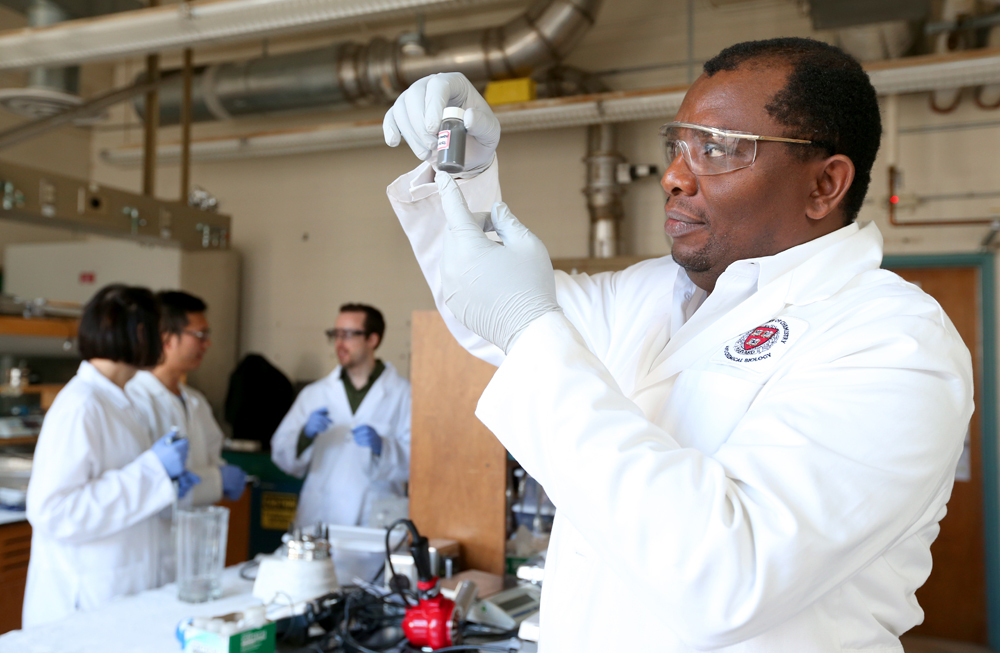

Martin Thuo likes to look for new, affordable and clean ways to put science and technology to work in the world.

His lab is dedicated to an idea called frugal innovation: “How do you do very high-level science or engineering with very little?” said Thuo, an assistant professor of materials science and engineering at Iowa State University and an associate of the U.S. Department of Energy’s Ames Laboratory. “How can you solve a problem with the least amount of resources?”

That goal has Thuo and his research group using their materials expertise to study soft matter, single-molecule electronics and renewable energy production. A guiding principle is that, whenever possible, nature should do part of the work.

“Nature has a beautiful way of working for us,” he said. “Self-assembly and ambient oxidation are great tools in our designs.”

One of the latest innovations from Thuo’s lab is finding a way to make micro-scale, liquid-metal particles that can be used for heat-free soldering plus the fabricating, repairing and processing of metals – all at room temperature.

The discovery was recently reported online in the journal Scientific Reports. Thuo’s co-authors all have Iowa State ties: Simge Cinar, a postdoctoral research associate; Ian Tevis, a former postdoctoral researcher who’s now chief technical officer at an Ames startup called SAFI-Tech; and Jiahao Chen, a doctoral student.

Ask about the discovery and Thuo says Iowa State is just the place for a new development in soldering technology. Back in 1996, a research team led by Iver Anderson of the Ames Laboratory and Iowa State’s department of materials science and engineering patented lead-free solder. That patent expired in 2013. But at its peak, the technology was licensed by more than 50 companies in 13 countries.

Thuo is hoping his heat-free soldering technology is just as useful. To try to help make that happen, he’s worked with Tevis to launch SAFI-Tech. Thuo said the company plans to locate to the Iowa State Economic Development StartUp Factory when it opens in the ISU Research Park later this year.

The project started as a search for a way to stop liquid metal from returning to a solid – even below the metal’s melting point. That’s something called undercooling and it has been widely studied for insights into metal structure and metal processing. But it had been a challenge to produce large and stable quantities of undercooled metals.

Thuo’s research team thought if tiny droplets of liquid metal could be covered with a thin, uniform coating, they could form stable particles of undercooled liquid metal. The engineers experimented with a new technique that uses a high-speed rotary tool to sheer liquid metal into droplets within an acidic liquid.

And then nature lends a hand: The particles are exposed to oxygen and then an oxidation layer is allowed to cover the particles, essentially creating a capsule containing the liquid metal. That layer is then polished until it is thin and smooth.

Thuo’s research group proved the concept by creating liquid-metal particles containing Field’s metal (an alloy of bismuth, indium and tin) and particles containing an alloy of bismuth and tin. The particles are 10 micrometers in diameter, about the size of a red blood cell.

“We wanted to make sure the metals don’t turn into solids,” Thuo said. “And so we engineered the surface of the particles so there is no pathway for liquid metal to turn to a solid. We’ve trapped it in a state it doesn’t want to be in.”

Those liquid metal particles could have significant implications for manufacturing.

“We demonstrated healing of damaged surfaces and soldering/joining of metals at room temperature without requiring high-tech instrumentation, complex material preparation or a high-temperature process,” the engineers wrote in their paper.

Thuo and the Iowa State Research Foundation Inc. have filed for a patent on the technology.

Thuo supported the project with faculty startup funds from Iowa State and funds from a Black and Veatch faculty fellowship. The project also included imaging work at the Center for Nanoscale Systems at Harvard University in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Tevis, of the SAFI-Tech startup, said the company is still testing the liquid-metal technology for electrical conductivity and mechanical reliability. He said the company is also developing the technology for product demonstrations.

Thuo said the project is a good example of his frugal approach to science: it should be practical, sustainable, inexpensive and all about innovating and solving problems.