This story was originally published by Donnelle Eller with the Des Moines Register.

Expecting a baby with the new year, Iowa State University engineering doctoral student Marty Haverly has been thinking a lot about the climate challenges future generations face.

Haverly and his wife, Julie, a senior business analyst at the Ames-based biodiesel producer Renewable Energy Group, think they have the opportunity to address those challenges head-on.

“We can have a hand in shaping our children’s future,” said Haverly, who is working with scientists to develop a fuel that could power our cars and warm our homes while actually cutting carbon emissions.

“Everyone wants to do good,” said the 26-year-old, a pragmatist who seeks to make a carbon-free fuel that’s price-competitive with fossil fuels. “We can have great intentions, but they have to be scalable and profitable” or they won’t be viable.

Haverly is part of a diverse group of Iowa engineers, scientists and researchers who are developing technology that could help transform the nation’s energy landscape.

The next big breakthrough could spawn new industries that drive not only Iowa’s economy but also the U.S. and world economies, said Sarah Nusser, vice president of research at ISU, which has attracted nearly $70 million for energy research over five years.”We have research that can create products that help our economy and can provide solutions to our most vexing grand challenges,” she said.

Imagine utility-scale batteries that could solve one of the most difficult energy problems: finding a low-cost way to capture the nation’s burgeoning wind and solar energy and store it for later use.

Or a wind turbine as tall as 801 Grand, the state’s tallest building, that captures a stronger, more consistent source of energy.

Or technologies that remove or store carbon dioxide, which is building in the atmosphere due to emissions from burning coal, oil and gas. Scientists say carbon is contributing to rising global temperatures.

Haverly is working with Robert Brown, an Iowa State University professor who leads development of ISU’s next-generation fuel technology.

“If you want to produce energy or any kind of product in our current economy, you’re going to emit CO2 into the atmosphere,” Brown said. “Growth is tied to CO2 emissions. But what if we can look at a technology that breaks that paradigm?”

Brown thinks the answer is pyrolysis, a process that rapidly heats biomass to create a new oil that can replace oil and gasoline. It also creates a byproduct called biochar that can store carbon while also enriching the soil.

Brown said agronomists working with his team say it’s similar to the carbon that’s found in Iowa’s rich soils and that came from 10,000 years of prairie fires.

He envisions building small power plants across the countryside, which would produce energy from crop residue like stalks and husks from corn or from perennials like miscanthus and switchgrass.

Joe Polin, a 28-year-old engineering doctoral student, works with Brown and Haverly to ramp up the technology at ISU’s BioCentury Research Farm. “This is a technology that’s getting off the ground now,” he said.

“A lot of these advanced bioenergy technologies are really important to creating jobs in rural America and creating value” for farmers, said Polin, who grew up in the small town of Tyngsborough in northern Massachusetts.

Developing batteries that are safe, cheap

Steve Martin, another engineer at ISU, is trying to find a way to create safer, low-cost batteries that can store large amounts of wind and solar energy.

He’s seeking to eliminate organic liquids that can be highly flammable in both existing lithium-ion and sodium batteries now on the market.

Those liquids are why some batteries have caused the popular “hoverboards” to start on fire. Their flammability is also why those batteries are less-than-desirable candidates for grid-scale wind and solar storage.

“You cannot have a four-story building full of batteries start on fire,” said Martin, whose team and his collaborators recently landed a $3 million federal grant to develop a prototype of an all-solid-state sodium battery.

Large-scale storage “has to be exceptionally cheap and exceptionally safe,” Martin said. He thinks the all-solid-state sodium battery he and his partners are developing will fit that description.

Sodium is widely available in nature, and is familiar as part of the compound sodium chloride, or common salt. Building the batteries from such an abundant element could slash costs. And overcoming challenges to make the batteries solid-state would make them safer.

It’s the kind of technology that could force entrepreneur Elon Musk to retool his $5.5 billion battery gigafactory in Nevada. “This is new technology,” Martin said.

Storage critical for increasing wind, solar

Renewable energy storage will be important for Iowa.

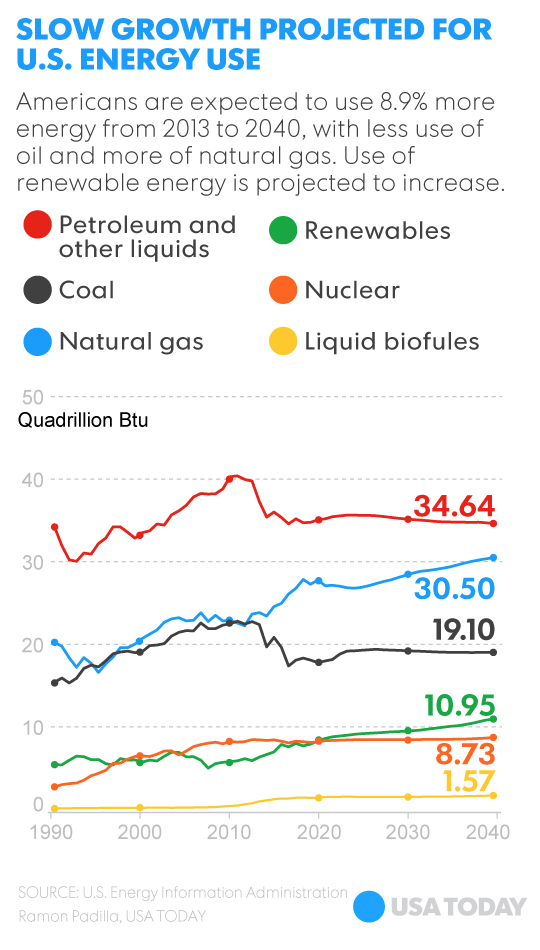

The state ranks fifth nationally for its energy consumption per capita, given its large manufacturing, farming and biofuel sectors, according to the U.S. Energy Information Agency. Iowa is the nation’s largest ethanol and biodiesel producer.

Iowa still gets most of its electricity from coal, although renewable energy is growing quickly. The state gets about 30 percent of its electricity from wind, placing it first in the nation. It could meet most of its electricity needs through wind by 2030, research shows.

Iowa’s solar possibilities are significant as well.

The Iowa Environmental Council says the state’s solar potential ranks fourth nationally, behind only Arizona, California and Nevada.

Nathaniel Baer, the group’s energy program director, said Iowa could “double and maybe double again” its wind and solar energy capacity over the next couple of decades.

“Could solar be 2 percent, then 5 percent and then 10 percent of our generation?” he said.

Mark Petri, director of the Iowa Energy Center, a state-supported group that helps researchers develop emerging technology, said interest in solar is spiking. Iowans are putting solar panels on farms, homes and businesses.

And several utilities are sponsoring community solar gardens that give customers a chance to buy a share, said Petri, whose group provides low-interest loans for renewable energy.

With greater adoption comes lower prices

Baer said greater adoption of solar, wind and other renewable energy will help drive technology advances and lower prices.

Baer said greater adoption of solar, wind and other renewable energy will help drive technology advances and lower prices.

Since 2009, prices for the average U.S. installed solar project have fallen 50 percent, and wind project prices have dropped about 30 percent, reports from the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory show.

“There’s no reason to wait for a breakthrough technology. We have technology. We just need to use it more,” Baer said.

As more wind turbines dot Iowa’s rural landscape, some might get much taller, Petri said.

Iowa State civil engineer Sri Sritharan is developing high-strength concrete wind towers that are as tall as the Ruan Building in downtown Des Moines and, with a turbine and blades, will push as high as Principal Financial’s 801 Grand Ave. building, at 630 feet.

Other scientists are pushing smart grid technology that can make better use of renewable energy and lower costs, Petri said. And some researchers are working with manufacturers to cut energy use.

“To be sustainable, we have to take these research ideas to the next levels,” said Petri, who noted that Iowa researchers often collaborate with scientists at the U.S. Department of Energy’s Ames Laboratory, located at ISU.

Haverly, the young ISU engineer, said the climate change challenges that future generations face are “very real to me now,” with the arrival of his first child on Saturday night.

“I have a lot of faith in where we’re headed,” Haverly said.