One Iowa State student’s research took her to Albuquerque, New Mexico to present at the Association of Firearm and Tool Mark Examiners annual training seminar. Laura Ekstrand, graduate assistant in mechanical engineering, has been conducting research with Iowa State faculty and the Ames Laboratory to explore new opportunities in forensics technology. Ekstrand’s research focuses on using data to compare marks left at crime scenes to the tools that may have created them.

One Iowa State student’s research took her to Albuquerque, New Mexico to present at the Association of Firearm and Tool Mark Examiners annual training seminar. Laura Ekstrand, graduate assistant in mechanical engineering, has been conducting research with Iowa State faculty and the Ames Laboratory to explore new opportunities in forensics technology. Ekstrand’s research focuses on using data to compare marks left at crime scenes to the tools that may have created them.

“The idea is, the suspect is going to, say, pry into a shipping container or something and they’re going to leave behind a mark with their tool they use… It’s kind of the nature of tools to leave scratches, and in fact, the whole reason why you can figure out which tool made which mark is because during the manufacturing process, the tools that make the tools that come in your toolbox leave marks,” Ekstrand explained.

Ekstrand, who earned her bachelor’s and master’s degrees in mechanical engineering at Iowa State, was tasked with finding a way to digitize the marks left by tools in a way that would allow them to be matched to a specific tool.

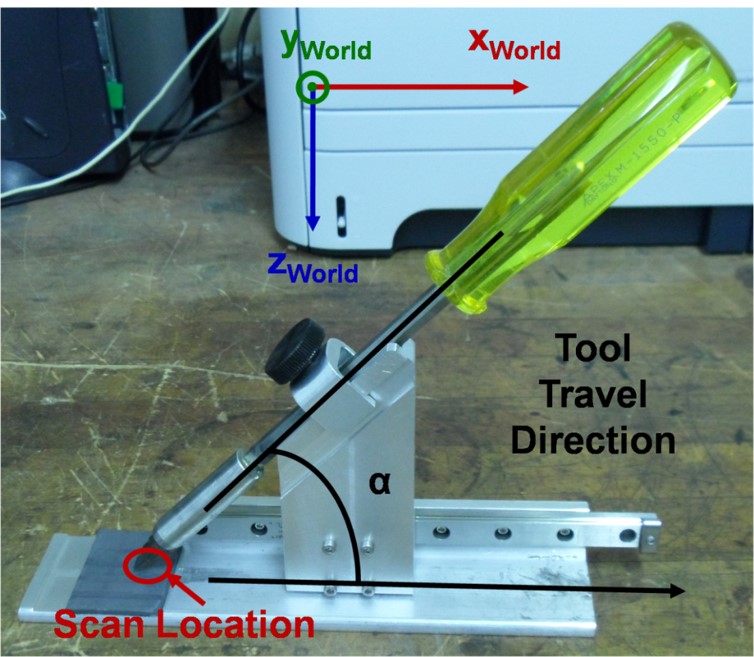

“The reason why this is an interesting problem is that’s something that the examiner can’t do. The examiner can make a lot of marks, but nobody really at the time had taken a screwdriver tip, digitized it into the computer, and used it to make marks. So that was kind of my role in this project, how can I get the screwdriver tip to make marks inside of the computer?”

By using linear algebra to project data points onto a flat plane, Ekstrand said, the researchers were able to study marks left by different screwdrivers.

“We can figure out not only which tip made the mark, but what angle it was made at roughly,” Ekstrand said. “There were no false positives, so we never had a match between screwdrivers that didn’t actually match in real life. That’s really good. We did have a couple of false negatives, so they were supposed to match and they didn’t.”

Ekstrand said the false negatives could be attributed to time-sensitive materials being used over the course of a long research process.

Ekstrand’s work, and other similar research, has the potential to aid in criminal trials. The nuances of the legal system, though, mean that forensic evidence does not always present a straightforward answer to the judge and jury.

“Their work is one part of a larger suite of evidence. The problem with court is that if you’re giving your professional opinion, the defense is going to try and find somebody that will cast doubt on that. That’s what the defense does; they’re going to cast doubt on what the prosecution says,” Ekstrand said.

At the AFTE training seminar, Ekstrand was able to present her work to forensic examiners and fellow researchers. The field of forensic research has broadened in recent years, partly because of increased government funding.

“There’s so much variation in the world of tool marks. It’s not like DNA. Everybody thinks that crime scene investigation is just DNA,” Ekstrand said. “A common misconception in the public is that you always get good DNA evidence and the error rate is so small. You don’t always get DNA evidence.”