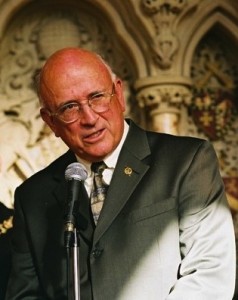

Iowa State engineering alumnus Bob Walkup will tell you, more than once, what he thinks about engineering and engineers.

“Engineers can do anything. It’s that simple,” he says. “That was my father’s motto, and it became mine. I truly believe it.”

Walkup’s father, Joseph Walkup, was the general engineering department head at Iowa State University from 1942 to 1973, and the person for whom the Joseph Walkup Professor of Industrial and Manufacturing Systems Engineering is named.

“His tenure was my entire childhood; he was a young man when he was appointed, and I remember visiting his office on campus as a small boy,” says Walkup.

The Walkup family’s confidence in engineering at Iowa State continues from Joseph’s example. Walkup himself graduated from the university’s industrial engineering program in 1960. His daughter Holly graduated with a degree in industrial engineering in 1983, and his granddaughter Emily is a freshman in engineering this year.

“Iowa State sold itself. It’s where my granddaughter wanted to go, and we’re so very pleased and proud,” says Walkup. “It’s interesting to me that the number of engineering students now is about the total student population of Iowa State when I attended. That’s an amazing amount of growth.”

Walkup credits his father Joseph not only for his confidence that “engineers can do anything,” but also for the discipline and organization it took for him to make it academically.

“When I was in high school, I was a bit of a jock. I was good in football, basketball, and track, and I didn’t think anyone cared about anything else. Boy was I wrong, and my father let me know in no uncertain terms,” says Walkup.

Joseph was so serious about improving his son’s academics that Bob didn’t participate in sports his senior year. It meant giving up basketball the year Ames High School won the state championship (1955).

“It wasn’t as severe as it sounds,” Walkup says. “My family had set these objectives for me, and it was my responsibility to perform. We were all raised that way back then. There was no question that I would follow my parents’ wishes.”

He enrolled in engineering at Iowa State in 1955. Just as in high school, study remained his primary objective.

“I studied. I don’t think I even dated. I never went downtown for a beer. I was either at home or at the library,” he remembers.

He said his father found him “relevant work” when he wasn’t in school, but it was also clear that it was meant to reinforce interest in finishing college.

“I worked one summer as a gandy dancer (track maintenance worker) on the Rock Island Railroad. It was hard, hot, tough work,” Walkup reflects. “I came home at the end of the season and told my father, ‘I don’t think I ever want to do that again,’ and his response was, ‘well then, you had better get to work’.”

He returned to classes with more determination than ever, and it’s something he has never regretted.

“I made only one mistake about engineering, and it was something I said when I was still a student,” Walkup says. “I remember telling someone how anxious and impatient I was about graduating and getting out into the working world because all of the really important inventions had already been discovered.”

As he talks about his 35-year career in the aerospace industry, working as an engineer and as an executive for Rockwell International, Fairchild Republic, and Hughes Aircraft Company, it was obvious he needn’t have worried about a shortage of problems to solve.

He says his career is an example of the resiliency of industrial engineering.

“I had the President of Fairchild Republic ask if I would like to come out and run its factory. He asked ‘do you know you how to build airplanes?’” Walkup remembers. He didn’t. “But I never said I don’t think I can do that job. I always said, ‘I’m going to have to learn some new things fast.’”

In the early 1970s, Walkup worked as an engineer at the at the U.S. satellite tracking station at Pine Gap in central Australia. “It was historic, really, the work we did there. It was instrumental to our government during the Cold War and the SALT II treaty negotiations,” Walkup says.

Engineering also kept him in the know when he served for three-terms as the mayor of Tuscon, Ariz. With the city’s major economic development programs, including a $200 million project for modern streetcars, his engineering skills gave him the background necessary to make important decisions.

“It really came to bear in the first time the city was involved in the design of a fairly sophisticated transportation project. It’s not something a city of any size gets to do every day,” says Walkup. “But they had a mayor who understood the project from an engineering standpoint. I found myself sitting in the boardroom of Rockwell International, discussing its contract for the propulsion system. A mayor with no engineering background would not have been able to carry that conversation.”

Most recently, the government of South Korea has just appointed Walkup “Korean Honorary Consul” serving the state of Arizona’s Korean population as well as Korean interests in the emerging trade, commerce, energy and cultural opportunities in the state.

“What I found throughout my career is that engineering, all of its disciplines, remains a vibrant, fascinating field. I learned something new and exciting every day.”

Walkup says the field has grown and changed since his father’s time, but his belief in the strength of engineering remains unchanged.

“I believe everyone should be an engineer,” he adds. “It’s an inspirational career, and it allows you to go through life discovering things and solving problems. It applies to almost every discipline, every walk of life. It’s essential to society.”