Accelerating environmental equality in rural communities, Kaoru Ikuma receives $3.2 million EPA grant

Author: Sarah Hays

Author: Sarah Hays

For most people, the thought of drinking recycled wastewater doesn’t seem appealing. But contrary to initial perception, water reuse, the method of drinking and using what used to be undrinkable water, is safe, clean, and healthy.

Engineers at Iowa State University are starting a project to normalize and accelerate water reuse for rural communities. Water reuse is already implemented in small ways across the nation, especially in urban areas, but society still tends to turn heads at the thought of drinking what used to be “unusable” water.

The Department of Civil, Construction and Environmental Engineering (CCEE) just received a $3.246 million grant from the United States Environmental Protection Agency for this project, called “Accelerating Technical and Community Readiness for Water Reuse in Small Systems” spanning four years. Iowa State is the lead institution, with associate professor Kaoru Ikuma as the principal investigator on the project. The team is also working with the University of Rhode Island and the University of California Berkeley.

“What we are going to do is focus on small, rural communities across the United States that tend to be really left behind from a lot of water policies and funding,” Ikuma said. “So how can we help accelerate their readiness to adopt water reuse if it looks feasible?”

Both cost curve and seasonal availability tools are being developed by the team to find out how they can make water reuse affordable and accessible for these communities.

“Technology, water availability, social acceptance, those will all dictate the cost of doing water reuse,” Ikuma said. “So we are trying to develop a cost curve to say how much it will cost for the community to recycle certain types of water.”

By collaborating nationwide, the team can ensure that case studies happen in various geographic locations across the United States.

“In this project, we consider taking what is traditionally considered waste or unusable water and turning it into something useable. This could be wastewater, rainwater, greywater, runoff, and a bunch of other types – and finding out the best use of each in a specific community,” Ikuma said. “Having collaborators nationwide is deliberate because the goal is about having a national scope for how we can help rural communities consider water reuse as an option.”

Windows of opportunity framework

It’s not always realistic to expect communities, especially those with few resources, to be able to dissolve their previous methods and switch to water reuse systems. This barrier is the basis of Ikuma’s project – Ikuma calls their framework “windows of opportunity,” hoping to spread awareness so that when the time is right, communities can choose to switch to a water reuse system.

“We call the tools we are creating a ‘windows of opportunity’ framework,” Ikuma said. “These rural communities don’t have a lot of money or resources, but there could be opportunities for water reuse if we introduce it to them at the right time. Suppose you introduce water reuse plans to smaller communities when their infrastructure is crumbling and they know they have to do something about it. In that case, it is the perfect opportunity for them to think 50 or 100 years ahead and consider the non-traditional water reuse process.”

Barriers for rural communities

Since most research in this area tends to focus on larger urban communities, there are many questions that the team has to answer.

“What end uses are people willing to accept? Do they want their water bill to be cheaper? Are they willing to pay extra? All of that tends to be focused on bigger scales and urban areas – so we don’t have a good sense of what people in rural communities want yet,” Ikuma said. “On top of that, there are also institutional barriers. There are many regulations you need to follow, but officials don’t really talk to the communities about that. So when you use water reuse, a lot gets lost in translation. How do we help with that?”

Not only does Ikuma study the impact water quality has on rural communities, but she also ensures that rural community research isn’t forgotten in the classroom.

“When we teach students to design systems and become environmental engineers, we almost always think about bigger, more urban systems with steady flow,” Ikuma said. “But in smaller systems, you have interruptions and various things happening; there might not be a person capable of running the plant, so the whole problem and human aspect are so different. I have always felt we are doing a disservice to our students when not teaching them that side.”

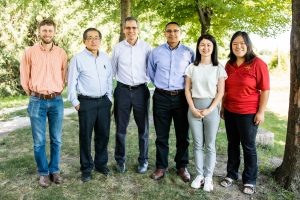

Ikuma has been passionate about helping communities with the quality and availability of their water for a long time – studying reuse regarding pathogen exposure just last year. Her previous work was a big inspiration for this project – but Ikuma knew this project was truly perfect for CCEE when new faculty with the right expertise was introduced, she recalls. Assistant professors Joe Charbonnet, Antonio Arenas Amado and Lu Liu joined the department within the last year, bringing their own technical knowledge to the project.

“This project aligns with our new faculty’s strengths here in the department – Lu is developing the cost curve, Antonio is researching water availability, Joe is using his technical background on water reuse, and I saw it as an opportunity to lift them up,” Ikuma said. “With these team-building projects, you can tell when it was meant to be. And I think this one was truly meant to be.”

The team is also joined by associate professor Chris Rehmann, professor Say Kee Ong, political science associate professor Yu Wang, University of Rhode Island’s Joseph Goodwill, Vinka Oyanedel-Craver, Todd Guilfoos and University of California Berkeley’s Michael Kiparsky.

Through Ikuma’s research, it’s clear that environmental justice is a top priority for environmental engineers. By educating and building tools for rural communities, and understanding that there are barriers to overcome, the team’s goal is to provide safe, clean water for rural communities in the most cost-effective and environmentally safe way possible.

“In this job, I can be as narrow-sighted as I want to be, but nothing says I have to be,” Ikuma said. “With all of this expertise in our department and a dire need for environmental justice, we are taking a broader, higher impact approach to help as many people as possible, as fast as we can.”