Keeping Piglets Warm this Winter with State-of-the-Art Heat Technology

Author: Sarah Hays

Author: Sarah Hays

In Iowa, pigs play a substantial role in our communities around the state. Two Iowa State University (ISU) Department of Agricultural and Biosystems Engineering (ABE) alums and one faculty member in the department have been researching a heating structure (microclimate) that will keep piglets warm at a rate that is healthy and efficient.

The trio recently got published in the Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute (MDPI) AgriEngineering journal for their state-of-the-art research. Their article is titled ‘Modeling and Assessing Heat Transfer of Piglet Microclimates.’

It all started with Steve Hoff, a retired professor in ABE, pursuing his master’s back in 1985.

“For my master’s work, I did some investigation in microclimates and published a couple of papers on that, with findings of the most efficient and best temperature for the piglets,” Hoff said. “After that, I started working with Ben, and he just took the research and accelerated it all.”

Ben Smith, a part-time lecturer at Iowa State and now a co-partner with Hoff on a start-up company for these microclimates, was a student of Hoff’s, and together they pursued the microclimate research.

“We took the models and the temperature findings and expanded it so we could start applying it to a lot of the different environments the industry uses to get an effective comparison,” Smith said. “The modeling work we did showed how every microclimate is different. From that, we found an ideal range that the environment needs to be to support the growth of the piglet and the best chance of survival because they are born with no ability to maintain their body temperature.”

When a piglet is born, it often stays with the mother, often known as the ‘sow.’ But a sow and a piglet regulate their bodies at different temperatures, so they need different heat levels.

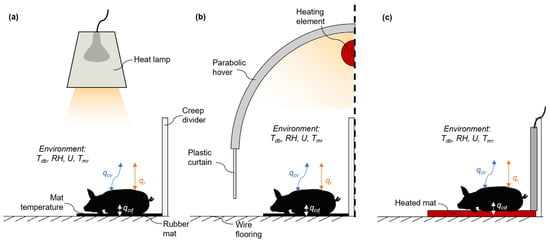

There are two typical methods for livestock microclimates. One of the most common is a heat lamp. While a heat lamp does provide heat, it tends to radiate heat in one sharp circle and only from the top. This can be problematic for the piglets because the hot circle can often be too hot from the top but too cold for the piglet’s side on the ground.

The second method, a heat mat, also raises the issue of the piglet only feeling the heat in one part of its body, except it is the opposite of a heat lamp. Instead of heat radiating from the top, the heat rises from the bottom of the mat, causing the piglet to feel too hot on the bottom and too cool on the top.

Both of these methods work and cost an affordable price. Still, they tend to use more electricity than the piglets need and waste heat by not containing it and providing inconsistent heat levels throughout their bodies.

“A heat lamp is the cheapest, and it is fairly successful at keeping piglets warm,” Brett Ramirez, an assistant professor in ABE also working on this project said. “Heat mats have a higher capital cost upfront, but over time are cheaper.”

Between these two microclimates, Hoff, Smith and Ramirez juggled the good and bad of both methods and analyzed research on a more energy-efficient, cost-effective microclimate, keeping the piglets warm from all angles.

“We identified how different devices have pros and cons toward the piglets throughout that lifecycle, from birth to when they are weaning from the sow, and showed that the more modern devices that control more variables can provide an ideal environment,” Smith said.

The team researched the ‘Haven Microclimate,’ a heat source invented by Amos Peterson, with a shield and infrared lighting. With the shield, heatwaves are contained, similar to the heat in a house. So while it is more of an investment, it doesn’t drain electricity as much as the other two microclimates.

“The Haven Microclimate costs more upfront, but in the end has a lot more benefits,” Smith said. “It utilizes an infrared heat source with a shield in front of it, so it directs the heat toward the piglet while also preventing any air drafts. There are curtains around it to prevent the air drafts.”

The Haven Microclimate saves many piglets’ lives, substantially reducing mortality.

“One of the big benefits of this Haven Microclimate is that out in the industry, it has shown to reduce piglet mortality by 20-22%, so that’s huge. So not only does it save energy, but it saves piglets’ lives,” Hoff said.

At first glance, it seems that the Haven Microclimate solely impacts the piglets, sows and the farmer’s costs. But there is another positive aspect of the Haven Microclimate that is important yet overlooked: its environmental impact.

Since the microclimate has shields and curtains, it spends less time exerting energy and, therefore, has less impact on the environment. The Haven Microclimate reduces typical microclimate energy consumption by over half – 52%, to be exact.

“This enhances the well-being of the pigs, helps to manage the cost of production and reduces our carbon footprint and energy consumption,” Ramirez said.

The Haven Microclimate may have started with livestock as the focus, but the trio is already starting to hear from people across the nation wanting to use the microclimate for other reasons. Recently, they already were contacted by the University of Miami for a potential project.

“This is an avenue that we hadn’t thought of, but a professor from the University of Miami contacted us recently, wanting to use our piglet microclimate for piglets raised for human organ transplants,” Hoff said. “It could be really important, so we are happy to be a part of it.”

The team is considering all the different ways that the Haven Microclimate can be helpful. In contact with many different colleges around the nation, the Haven Microclimate seems to have potential that the trio may not have anticipated, but are ready to solve.