A new grant is helping one CBE professor light the way to better semiconductors

Author: cbecomm

Author: cbecomm

A $430,000 grant from the Air Force Office of Scientific Research (AFOSR) is helping Building a World of Difference Faculty Fellow and assistant professor Luke Roling develop new materials to build next-generation microelectronic devices.

The limits of silicon

The majority of consumer products we use every day, from your cell phone to your dishwasher, rely on semiconductor-based microelectronics to operate. Microelectronics serve as the “brain” of these devices and consist of a large collection of transistors along with other electronic components that control the flow of electrons to process, store and receive information. The majority of microelectronics are made from silicon.

Early microelectronics had only a few thousand transistors but now can contain billions. This increase in complexity is thanks to the ability to use silicon to shrink the size of transistors, which allows our electronic devices to become faster, more powerful, and more compact.

However, as Roling explains, “There are limitations to how small we can make silicon transistors, and we’re starting to reach those limits because of the energy required and heat generated with traditional electronics technologies.”

The next generation of semiconductors

Next-generation semiconductors could avoid this limitation by transmitting information using light instead of electrons.

Roling explains, “The idea is to replace silicon transistors with a material that can more efficiently use light to convey information. Silicon has worked well in our existing technologies but doesn’t have ideal optical properties for emitting light. A premium candidate for this is a germanium-tin alloy, because germanium has much more efficient light-transmitting properties that can be optimized and controlled by incorporating tin.”

Germanium-tin semiconductors could dramatically advance our computing and communication technologies. However, there is a problem.

The problem

On an atomic level, germanium-tin systems are relatively unstable; as a result, only a small amount of tin can be infused into large quantities of germanium.

“Ideally, we want to control the amount of tin incorporated into germanium from a few percent to nearly 50 percent. We aren’t able to make and fine-tune high-quality germanium-tin devices across that range right now, but my research can help get us there,” says Roling.

Roling’s project, which is being funded over the next three years by AFOSR, aims to understand how germanium and tin, along with silicon, interact with each other on an atomic level and shed light on how to promote and control the amount of tin that is incorporated into germanium.

The insights from Roling’s project could help scientists design and produce next-generation photon semiconductors that can be integrated into existing silicon-based platforms.

Using computers to find a solution

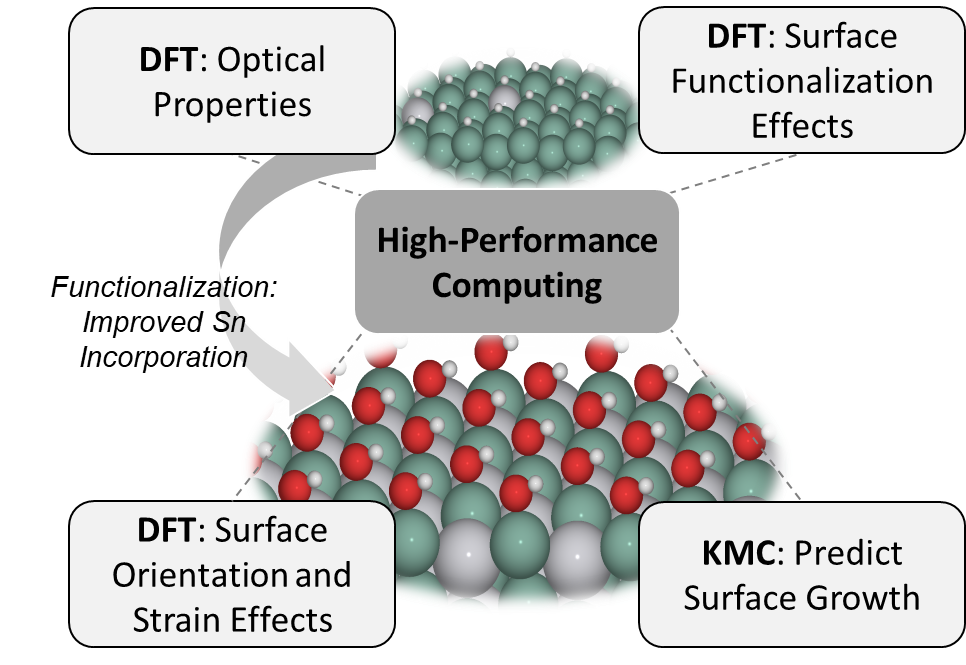

Roling’s research group exploits powerful computational tools to create predictive models of materials and systems.

“We’re going to use advanced computational chemistry toolkits to understand how germanium and tin interact on an atomic level. With these fundamental insights, we can then engineer systems and surfaces by introducing some stabilizing agents into the environment and controlling the amount of tin we can incorporate into germanium,” says Roling.

Once Roling and his research group identify some rules of interactions on an atomic level, they will conduct additional computational simulations to identify strategies that could be used experimentally to make germanium-tin materials.

From there, Roling’s group will collaborate with Herbert L. Stiles Faculty Fellow in Chemical Engineering and associate professor Matthew Panthani’s research group to test their strategies on real materials in the laboratory to synthesize germanium-tin materials.

Lighting the way with fundamental science

Although the research being conducted by Roling’s group focuses on fundamental interactions between atoms in a material, the new knowledge it creates could be used one day to create faster, more compact laptops, smartphones, gaming systems, and more.

“There is just so much potential here, but before we can reach it, we need to understand the fundamental science, and our research will help us do that,” says Roling.