ECpE receives NSF grant for neurodegenerative disease treatment using “mini-brain”

Becoming well-known and often discussed in society, scientists are learning more and more about mental illnesses — where they come from, their impacts and how to treat them.

The methods of treating mental illnesses are varied, some more serious than others. In certain circumstances, brain surgery or medications are required. Brain surgery is known to be a fairly invasive surgery, with a long recovery time and a time-consuming procedure.

In the Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering (ECpE) at Iowa State University (ISU), Associate Professor Long Que and Anson Marston Distinguished Professor David Jiles are running experiments introducing magnetic stimulation blended with drug treatment as a form of non-invasive treatment for patients suffering from certain mental illnesses — potentially preventing brain surgery for many patients.

The team recently received a grant from the National Science Foundation for their groundbreaking research on this topic, working with Donald Sakaguchi, a neuroscience professor at Iowa State. The team is erring on the side of caution in this experiment, so for this proposal, they are studying the effect of magnetic stimulation on the brain using a “mini-brain,” or a brain-like neural tissue that sits on a chip.

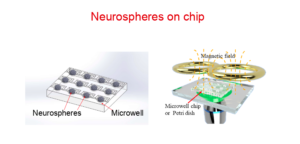

This “mini-brain” is made up of hundreds, or thousands, of neurospheres — a sphere containing thousands of different cells. The team can use the neurosphere, or “mini-brain,” to practice pinpointing magnetic rays to certain parts of the “brain,” and therefore see if, in a real brain, the magnetic stimulation would be effective.

“The purpose of this project is to mimic a brain by having a mini-brain on a chip,” Que said. “Of course, we could never be able to mimic a real brain on a chip, given its tremendous complexity. The major part of this project is the initial creation of that chip. Then, we are going to start two things. The first one is to work with Dr. Jiles to apply the magnetic stimulation to stimulate this ‘mini-brain’ on the chip. The second part is to start the drug effect.”

This project is a starting point for a huge innovation. After it is complete, the chip and neurospheres on it will be ready for testing.

The chip can fit hundreds of neurospheres, or “mini-brains,” on it. The chip itself is roughly a fourth of the size of an average credit card.

Once the chip is complete and the mini-brains are secured on it, the testing can begin. Magnetic stimulation is a known treatment for mental illnesses, and medications are as well. Both drugs and magnetic stimulation focus on stimulating the brain, specifically a part of the brain called the amygdala — which when stimulated is known to reduce certain mental illnesses. By combining the two and stimulating the amygdala together, the team hopes to see even better results.

“The basic idea is like this: You make a mini-brain to mimic a real brain on a chip, establish the model for a neurodegenerative disease by applying specific pathological proteins, then study the diseased mini-brain response under three situations — one is the magnetic field stimulation; the other is drug treatment; and the third is the combination of magnetic field stimulation and drug treatment” Que said.

The team’s device and project will eventually target several mental disorders. But right now, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved treatment for Obsessive Compulsive Disorder (OCD) and chronic depression.

According to Jiles, many members of the military are enthusiastic about this device. While it is not yet confirmed for treatment of Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), a common mental disorder stemming from traumatic experiences, PTSD treatment with this device would be extremely helpful for the military.

“This has been approved by the FDA for obsessive compulsive disorders and depression,” Jiles said. “We are looking at it for PTSD for the military. A lot of people in the military are very eager to have this done for them — because, being in the military, they can suffer from many mental disorders like PTSD.”

The drugs to be combined with magnetic stimulation tested on this mini-brain are drugs that are commonly used for mental disorders/illnesses today. The team already has access to the medications and the magnetics — adding them together is the next step.

This project seems groundbreaking, modern and new — and it is — but the team has actually been pursuing it for years. They submitted proposals for grants in many places and received rejection, but never stopped trying.

After some time, the project was jump-started by the Office of the Vice President for Research.

“Probably two years ago, we received some funds from the Office of the Vice President for Research for this proposal,” Que said. “We want to thank them for giving us some initiative, and that’s why we can successfully do what we are doing today.”

Where they are today, in the chip-creation stage, may be one of the most important pieces of the project overall.

“There’s basic science in this, and then there are applications,” Jiles said. “A lot of the basic science still needs to be done, which is why I think NSF has decided to support this. But then we also think about the transition from science to practice in the general population.”

The key about this project, when looking at the bigger picture, is that people will be able to be treated for mental illnesses at a more affordable price, for less risk and less time commitment, at double the effect.

“This is a non-invasive treatment, which I think is very valuable, because you know, if you have someone that has a problem with their brain, you could do brain surgery, but that is risky,” Jiles said. “So now you can do a magnetic sort of treatment where you would be able to treat a lot of people without being invasive. Even if it for some reason doesn’t work for a certain mental illness, then that’s fine, but it’s worth a try before doing brain surgery.”

Since the team is working with the “mini-brain” right now, they are trying to recreate a mini-brain with a disease to accurately test the impact of the drug and magnetic stimulation.

“For this project, we tried to have a disease model to evaluate the effect,” Que said. “We are going to continue gradually, step by step. This grant is more specifically for the mini-brain; it is a step toward the end goal.”

This grant from NSF is set to be a three-year grant, beginning in August of 2020 and ending in July 2023.